PRIMARY BUYER TYPES AND MOTIVATIONS

First and foremost, we ought to acknowledge the existence of different buyer types. Many sales and business development professionals often have extensive experience with different client behaviors. However, not every lawyer is aware of buyer typology, which is based on distinct behavioral patterns.

Derived from Thomas Nagle and Reed Holden’s works ― arguably ― there are four primary buyer types in B2B negotiations: 1) price buyers, 2) value buyers, 3) convenience buyers and 4) relationship buyers. (I think there could even be eight distinct buyer types, but, for the purposes of this article, four primary categories will suffice.)

Second, one of the underlying reasons for idiosyncratic buyer behavior rests with motivations. According to psychology literature, human motivations prime behavior, set up perceptual frames and participate in goal setting. Hence, during sales negotiations, client behavior will be driven by their motivations and goals.

Without getting into the weeds of psychological needs, motivations and goal facilitators, we should understand that each buyer type assigns disproportionate value to different aspects of service provision. From a client’s perspective, that which facilitates movement toward a worthy goal is valuable — everything else is irrelevant. Therefore, some components of your current service offerings will be perceived as central to one buyer type while mostly tangential to another

buyer.

ADJUSTING VALUE ACTIVITIES AND VALUE ELEMENTS

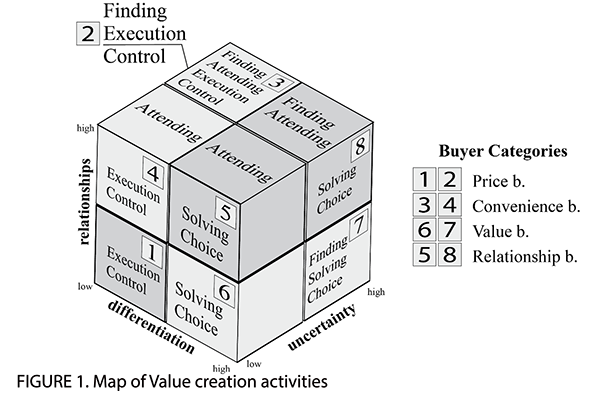

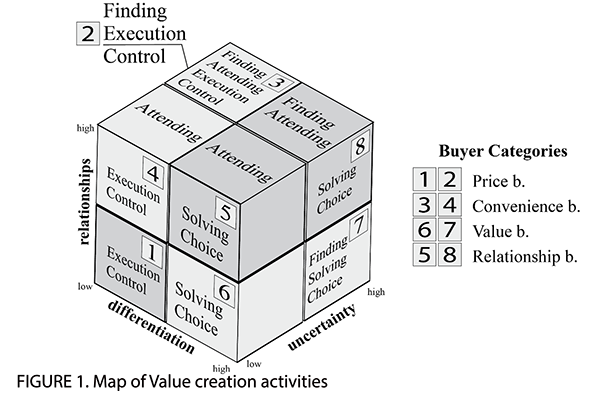

Two professors at the Norwegian School of Management introduced the concept of a value shop. With regard to professional service firms, my analysis suggests the following six value activities to be key: 1) problem-finding and acquisition, 2) attending, 3) problem-solving, 4) choice, 5) execution, and 6) control and evaluation. Figure 1 exhibits mapping of value activities to primary buyer categories.

Note that all six value activities may be important to the client in principle. However, if necessary, and the fees have to go down, value activities pertinent to their respective octants are typically the ones to be altered or dispensed with last.

Consider a typical price buyer (octants 1 and 2 in the figure) that arrives self-prescribed. They know exactly what they want from their law firm, how the services ought to be provided, who should be involved, when, why and how the process should unfold. Such behavior often manifests during repeat, low-complexity engagements, especially when buyers themselves have (or have unrestricted access to) expertise, connections, insight, etc. In such a scenario, this buyer couldn't care less for any value activities other than Execution and Control (octant 1). The finding value activity is worthless for self-prescribed buyers, too.

Even though this may be a standard procedure at your firm, it makes no sense to provide the other four value activities free of charge for this client. The perceived value will be negligible, while their provision is going to make your firm less profitable — not to mention professionals’ frustrations.

Adjustment of value activities is the first rapid way of improving value creation and capture at your firm. An additional way to enhance your service offerings rests with value elements. A well-known consulting firm, Bain & Company, published a list of 40 elements of value. Juxtaposing these value elements with the current components of your offerings may prove beneficial.

Consider a client that positively responds to services that are provided in a manner that supports, protects, connects, relates, includes other people and helps reach consensus ― a typical convenience buyer (octants 3 and 4). The following value elements (per Bain’s value pyramid) are likely to make your offering more

valuable to this client: responsiveness, commitment, cultural fit and reputational assurance.

Service offering design (SOD) implies creation, revision and fine-tuning of both new and existing offerings and service lines.

In addition, the most desirable value activities for the convenience buyer are most likely to be attending, execution and control — perhaps, some finding as well. Problem-solving (generating and evaluating alternative solutions) and choice (choosing the best-fit solution given the context) can be removed or downplayed first if necessary.

Obviously, some value elements and value activities may not make sense in the context of particular offerings. However, knowing what is valuable in principle allows partners and business developers to adjust the service offering on the go during client pitches. The details must be worked out in advance, of course.

SELECTING PROFESSIONAL SKILLS

The last quick intervention rests with matching lawyers with buyer types and type of work. It goes without saying that a lawyer must be competent. However, apart from technical expertise, there are also soft skills to consider. Hence, it’s worth knowing that every professional has natural strengths, personal preferences, professional proclivities and personality traits.

The overall quality of the service provision hinges on the professional’s technical ability: “I can do it;” willingness to do it well: “I really want to do it;” and commitment: “I will commit myself to doing it.” Because clients typically aren't great at evaluating the technical quality of the work ― from the client's perspective ― the latter two are essential. Therefore, personality assessments may be of significant help in illuminating the willingness and commitment requirements.

For example, because motivations shape our perceptual frames, a lawyer who really enjoys new ideas, strategic thinking, and dynamic, flexible environments might find themself at odds with a typical price buyer. A professional who prefers consistency, stability and discipline might be a better fit for such a client.

Each individual has a unique combination of different personality traits, preferences and natural strengths. While it is possible to fit some square pegs into some round holes, natural fitness requires less effort. The consequences of continuous mismatch between the lawyer and client engagements often result in professional demotivation, lower service quality and ― as a result ― lower profitability of the firm.

GOING FORWARD

There are three quick interventions through SOD that may improve your firm's performance. First, identify professionals who can, want and will commit themselves to doing the work well because of their personality traits, interests and natural strengths.

Second, assess which buyer types your firm has most/least success with. Identify which value activities (as outlined in Figure 1) you may wish to add/remove or reduce/amplify for particular clients. Make sure you have buy-in from respective attorneys and lawyers on these changes as well.

Finally, explore value elements to identify additional opportunities to add/cull offering components for certain buyer types. For example, if you have a case management software with a fancy client dashboard that has all sorts of enhancements to it, offer your clients access. Price buyers in particular will be ecstatic

about the ability to track progress — even for a fee.

The bottom line is straightforward: Charge clients for that which they perceive as valuable and prune activities and components that they deem irrelevant. To figure out what is recognized as precious, all we have to do is understand how our clients see the world. Sometimes, this is easier than it seems — especially for lawyers who already wear spectacles with the same perceptual lenses as clients.