According to Chris Johnson of The American Lawyer, “Big Law profitability is massively overstated and

… some firms generate virtually no profit at all.”

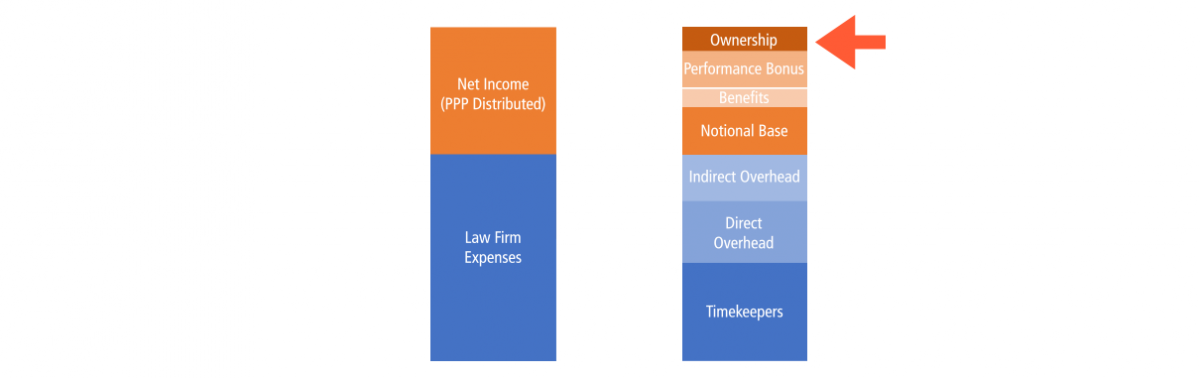

So, it’s more useful to understand the profitability of a timekeeper and a matter. If we understand these, we

can also calculate the profitability of a client, a practice, an office or an industry.

ASSUMPTION CONSUMPTION

There are a number of assumptions embedded in the analysis of timekeeper and matter profitability, and it cannot be

overstated how critical they are to influencing and/or understanding the result. In most cases, there isn’t a

clear right or wrong approach, but absent a common understanding, the mismatched expectations will lead to unrest

and unnecessary strife.

For example, does the firm measure performance on a cash or accrual basis? The latter is embraced by other business

segments because it can provide a more robust understanding of profit contribution over time. How will the firm

account for overhead expenses? Some mete out all costs in exhaustive detail; others ignore organizational costs that

partners can’t control. Do we assign lawyers based on capability and capacity, or does a busier lawyer get

more assignments?

How we account for lawyer utilization can present a disproportionate, and quite possibly false, read on timekeeper

profitability. Do we treat lawyers primarily engaged in rainmaking as more expensive than those primarily billing

time — even when those billing time would otherwise be idle without the rainmakers?

The combination of these and related assumptions will produce different results, so it’s important to

understand the business purposes for which each calculation is most helpful. As firm information systems grow in

sophistication, it’s common for leaders to be presented with different dashboards depending on business

purpose. Profit can be influenced and measured at multiple stages of the legal services delivery process, so

it’s important to provide analysis and decision support information in a way that’s easily understood

and digestible for the intended audience.

STRATEGIC PRICING (OR PRICING FOR PROFIT)

A key opportunity precipitated by a deeper understanding of profit is to be more strategic in pricing legal services.

Traditionally, law firm pricing has been set from the inside out, or by setting a price that covers the law

firm’s expenses and generates a healthy profit, often independent of what the market might be willing to pay.

As clients have flexed their buying muscles, law firms have had to embrace what every other business segment long

ago realized — value is defined by the buyer.

When sophisticated buyers of legal services know they can buy at half price and at greater quality than which they

once purchased from a traditional law firm, the endgame for the law firm is either obsolescence or adaptation. But

when adapting means lowering prices to meet market realities, this doesn’t have to mean lower profits and

smaller distributions for partners. By understanding what drives profitability, lawyers can re-engineer the work to

make money even when revenue is flat or declining.

Law firm leaders must link pricing to profitability. Rather than maximizing hours, or even rate, the goal is to

maximize profit. There are numerous levers available to partners to boost matter profitability, including staffing,

technology and automation. Similarly, there are numerous ways to boost firm profitability, including high

utilization, high realization, client retention and client penetration (aka cross-selling). The critical adjustment

to the art of pricing is knowing what the market is willing to pay for a service. Without this

knowledge, it’s sheer luck when the price charged is roughly equivalent to the client’s perceived value.

It’s not uncommon to hear a smug senior partner boast, “My rates have never been challenged by a

client.” It’s also increasingly common for a sheepish partner to lament, “My client apparently

doesn’t care about quality; they just want lower rates.”

What these both have in common is a lack of understanding of market value. When a client has never complained about a

price, it usually means the product is underpriced for the value delivered. When a client fixates solely on price,

it usually means the product is overpriced for the value delivered. As we incorporate profitability metrics, we can

shift away from a goal of selling as many hours as possible at the highest rates possible to a goal of maximizing

profits — even if this means raising or lowering the price or spending more or less time delivering the work.

REWARDING PROFIT NOT PRODUCTION

A discussion of profitability is an interesting but futile academic discussion if the partners don’t act

accordingly to change their behavior. In many law firms, there’s a clear recognition of the importance of

profits over hours, but there’s no incentive to change focus. Partners continue to make choices that,

unfortunately, pit the firm’s long-term financial interests against their individual interests. It

doesn’t have to be that way.

Managing partners often exhort their partners to act in a “firm-first” manner, which is an

acknowledgement that the partners have a choice. Instead of offering a choice of acting for or against the

firm’s interests, the choice for partners should be between maximizing one’s compensation by furthering

the firm’s interests or limiting one’s compensation by acting selfishly. The culture might not allow

de-equitization or ouster of a partner who refuses to collaborate. However, the compensation plan can certainly

withhold rewards for those who take more from the firm than they give. It’s the responsibility of management

to align what’s good for the partner with what’s good for the firm. Asking partners to find and then

pursue this path on their own is simply poor management.

It’s also important to note that not all partners are motivated by financial rewards. A compensation plan also

serves as guiding principles for what it means to be an owner of the firm and it helps to manage expectations by

linking rewards with actions. Modernizing a partner compensation plan can be time-consuming and cumbersome. Even

when there’s a clear vision of the end state, it might take a few years to implement because of the risk of

disruption. Nevertheless, it’s critical to incorporate measures of profit in partner compensation.

The most critical aspect of a partner compensation plan — and a goal that must be maintained throughout any

adjustments to formulae, processes or dashboards — is transparency. Whether the plan is formulaic or

subjective, open or closed, driven by an elected committee or by senior management, the most important goal is for

the plan to provide clear guidance to partners as to what rewards will ensue when they engage in certain behaviors.

The goal is not merely to reward profitable behavior, but to drive it.

This is not a task for the lighthearted, which is why so many law firm leaders avoid it. However, it’s the role

of management to align what’s good for the partner with what’s good for the partnership. Anything less

just “kicks the can down the road” to the next management regime. In this case, it’s probably

better to accelerate the arrival of a new management team than to allow the firm to languish under an outdated

compensation plan that often ignores profitability — and may even penalize it.

BUILDING A PROFIT CULTURE

Given law firms’ longstanding focus on measures of production, it may take some time to build momentum to adopt

measures of profitability. It’s important to move thoughtfully in order to avoid significant disruption. With

a hat tip to BigLaw Chief Financial Officer Madhav Srinivasan for offering insights based on his lengthy tenure in

the profession, we suggest firms take a multistage approach to incorporating and adopting profit.

- Measure. Firm leaders will work through a variety of approaches for measuring profit, sometimes behind the

scenes. While it’s helpful to have a mandate from the partners, it’s not necessary. Once a suitable

model is ready, it’s important to embrace change management principles to gain buy-in.

- Monitor. Once established, the profit measures are included in the firm’s financial systems and

reported, often in selected and targeted areas. Management provides targeted education to help understand how

the profit measures can be used.

- Manage. As profit measures become more ingrained, management can shift to sharing deeper insight into the

underlying drivers of profitability and providing training to help partners make better decisions.

- Master. At this stage, all partners have had intensive training and are expected to know and incorporate

measures of profit into their decisions, e.g., pricing, staffing, etc. Where partners fall short, corrective

action is taken.

- Motivate. Some partners will change behavior only when there are economic benefits or consequences in the

compensation plan. For those not motivated solely by financial considerations, the compensation plan linked to

the annual business planning process can serve as an excellent roadmap for incorporating more profitable

actions.

THIS IS ONLY THE BEGINNING OF THE JOURNEY

As law firms develop more sophisticated approaches to measuring profit, it will become easier for law firm leaders to

begin thinking differently. Rather than a one-time calculation, profit becomes a metric that can only be measured

over time. Profit can also incorporate multiple independent variables that don’t easily fit into today’s

simple models. Here are a few examples:

Today’s law firm measures and influences matter profitability by adjusting pricing and staffing to

achieve the optimal profit. Tomorrow’s law firm will consider the high cost of client acquisition (aka

selling, rainmaking) in its profit calculations and adjust pricing to win repeat engagements, forgoing some

short-term profits to secure a more stable future.

Today’s law firm often treats timekeepers as a fungible commodity where the goal is to reach maximum

utilization. Tomorrow’s law firm acknowledges that an expert who can deliver a certain task flawlessly

shifts over time from a competitive advantage to a competitive risk, i.e., when eventually no one else is

capable of doing that work. As a result, tomorrow’s law firm will consciously remove and rotate

expertise periodically to diffuse risk and spread experience, even if doing so dilutes profitability in the

short term.

Today’s law firm often treats process improvement as a necessary evil, because it can lead to billing

fewer hours. Tomorrow’s law firm marries process improvement with strategic pricing to proactively

offer fixed fees for as many services as possible, thereby ensuring a profit even as the market demands

lower pricing.

In the journey toward adopting a more modern sense of law firm profitability, there will be a number of roadblocks,

detours, diversions and shiny things to capture your attention. Don’t be dazzled by technology tools, crippled

by recalcitrant partners, or awed by complexity. As with all successful journeys, it starts with a few simple steps

in the right direction. We can’t go backward, but we can learn the way from those who have made this trek

before us. It’s time to get started.